The Next Era Of Cloud-Based Software Subscription Models

How cybersecurity sales models are transitioning to the next frontier

The software industry has changed a lot over the decades, and, no, I’m not talking about the development process or the engineering of it, though that’s another story. No, today, I’m talking about the selling of it - how it gets in the hands of paying users at scale. This is a key piece of fundamental knowledge when investing in software companies, as the sales model transitions over the last decade creates initial headwinds but turns into tailwinds thereafter. Understanding these transitions and knowing when they shift from headwinds to tailwinds is crucial to the growth story and, thus, your investments.

I remember my early days of graphic design and how one went about obtaining Adobe’s Photoshop and InDesign software. It was individual licensing per install and cost thousands of dollars per product. Of course, it was a one-time payment, something younger users today don’t even remember, but I guess I’m aging myself. This was also consumer-facing, not enterprise-facing, but they both seem to have moved in lockstep toward subscriptions in the modern era. Anyway, what I’ve focused on recently is that even with the move to the cloud over the last decade and a half and the more (relatively) recent transition to subscription payments for products, there’s another shift happening in the software industry. And while it’s not a “new” concept for those privy to the sales side of the enterprise software industry, it’s starting to become more pervasive and create financial shifts for the companies I cover and invest in.

After forgoing perpetual licensing at the start of this decade, where clients would buy the product upfront and then pay a nominal fee each year for maintenance (the enterprise equivalent of my Adobe example), software companies have continued to adjust to the new way of cloud-based life. And it’s not because “the cloud” came on the scene five years ago (it’s not that new). The “slow” adoption (relative to the technology itself) is mainly on the customer side, not the vendor side, as customers were (and still are in some pockets) more comfortable with on-prem (a data center located on the customer’s premise aka the private cloud) server utilization rather than breaking the firewall and connecting to the public cloud. However, with SaaS (Software-as-a-Service) becoming increasingly commonplace for start-ups and tech-forward businesses, selling software for a lump sum upfront, while the customer hosts and installs it, has become an archaic method of transacting at the business level (high volume).

One-time negotiations for a huge check up front, and then having to install it on the customer’s resources (another pretty penny) created a long sales cycle, not even considering the proof-of-concept standup time. It also created “lumpiness” in the software vendor’s business. This lumpiness in revenue was caused if a deal didn’t close by the end of the quarter, leading to a meaningful amount of revenue not being recognized in the reported quarter, resulting in missed investor expectations, to shareholders’ chagrin.

However, as the cloud became more widely accepted for hosting a vendor’s software and then offering it from there, the sales cycle accelerated. Not only could proof-of-concepts be more efficient by proving it out without utilizing customer resources (read: little risk), but the sales model shifted along with it. “Let us provide the hosting and the product, you just pay small, even payments for as long as you use it.” Another central advantage of cloud-hosted setups is the vendor takes responsibility for upgrades and maintenance of the software product. This is one less cost the customer has to handle, unlike an on-prem solution. And thus, the enterprise subscription model became the new sales model.

But before going further, I’ve seemingly gotten this far without addressing a somewhat glaring question: why not simply make customers pay using the subscription model with on-prem solutions?

The answer is a bit technical, but the bottom line is on-prem solutions often don’t face the internet, and thus, usage and licensing cannot be verified. This is why perpetual licensing was the method of choice: pay us up front, and the license essentially won’t expire since we (the vendor) can’t monitor it anyhow. Whereas the cloud-hosted variety, while also not necessarily internet-facing, is controlled by the vendor, and the usage and licensing are controlled - there’s no way to work around it.

Now, this didn’t mean every customer was on board with it. Those with sensitive data, misplaced security concerns, and other technical roadblocks didn’t jump on this bandwagon. It has taken years for many enterprises to become comfortable with this idea and to relearn outdated thinking with forward-thinking approaches. The technology industry is not a forgiving place most of the time, so falling behind means becoming irrelevant in many cases. Granted, government contracts and things of that nature are usually the last place to adopt new methods, but there’s no excuse, only erroneous thinking and poor planning, when the reward outweighs the risk.

Government contracts aside, this transformation of software delivery and purchase has also pervaded the consumer level. The Adobe software I mentioned at the beginning of this article is now available as a monthly subscription, eliminating the upfront financial burden.

At this point, you might be saying, “Well, yeah, just look at Netflix and Prime and Hulu, etc., they’re all just a monthly subscription.”

However, there’s a significant difference between streaming a movie and providing an enterprise-level software solution at scale, with security being top of mind. This is why it might seem obvious in terms of how money is now exchanged, but it has neither been like this for most of the software world, nor has it been a quick transition, contrary to popular belief.

Now, add to this the need to integrate AI, and there’s no longer a choice but to go to the cloud, leveraging the massive data piles of many vendors to enhance a company’s protection (cybersecurity), database efficiency, or AI assistants (coding, research, etc.).

And AI is likely driving the recent migration there. Only now, in 2025, is the technology world expected to be a majority cloud-based environment.

51% of IT spending is shifting to the public cloud (Source: Gartner)

The public cloud will replace traditional solutions for apps, infrastructure, business process services, and system infrastructure by 2025, compared to 41% in 2022.

As fast as technology moves, it only moves as fast as people are willing to adopt it. And with adoption now reaching critical mass, the time to again move the first down markers for the sales model has arrived.

Real World Sales Transitions

One of my most covered transitions from perpetual licensing to subscription licensing was CyberArk CYBR 0.00%↑. This process was counted in years, not months. And it wasn’t due to poor execution or CyberArk’s strategy. In fact, CyberArk was one of the most well-executed transitions I had seen. This type of move, again, is at the customer’s pace, and shifting a technology culture from one of “I own everything right here in my data center” to “I’m plugging into a ready-to-go and stood-up solution” takes a bit of willingness and work. The transformation from on-prem perpetual licensing to subscription-based cloud-hosted products had (and continues) to be done carefully and methodically.

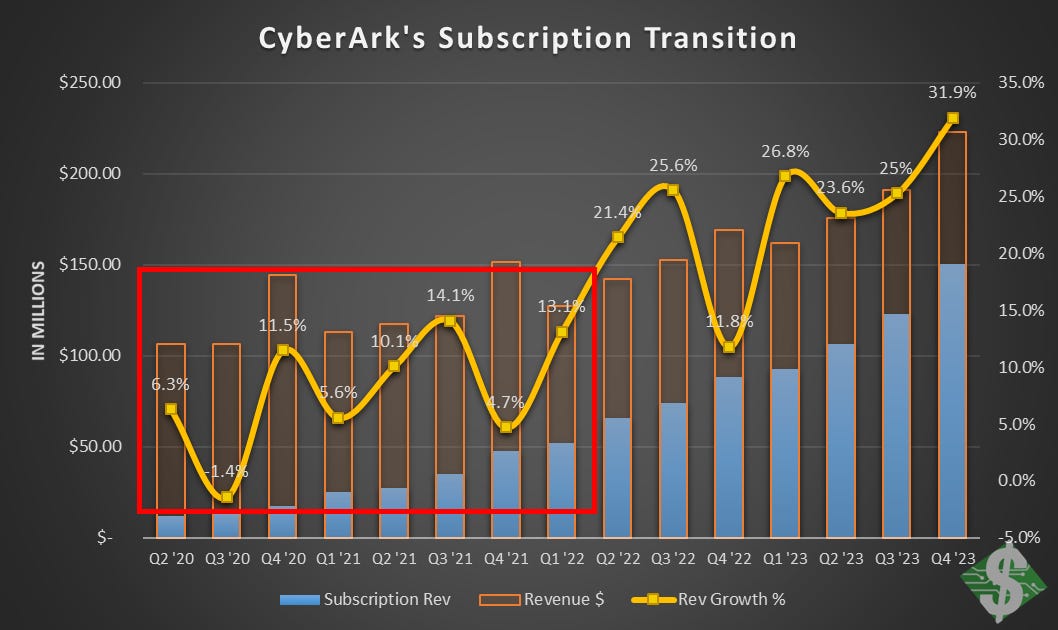

As you can see above, when management began going full force into selling subscription licenses and converting perpetual into subscription, revenue growth remained stagnant. As it began to reach a tipping point, where roughly 50% of revenue was coming from subscriptions, revenue growth started to lap the conversion time period where headwinds were, and saw growth accelerate.

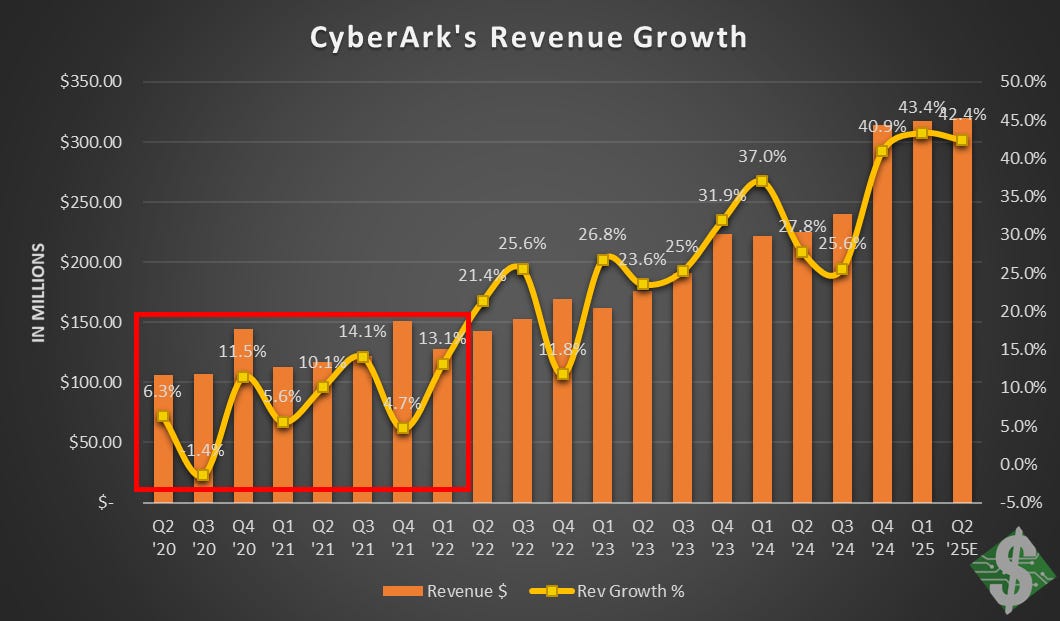

Since then, revenue growth has accelerated significantly (shown in the chart below). Granted, it has had an acquisition in that time period, but it didn’t close until halfway through the Q4 ’24 quarter. The growth in 2024 continued to accelerate year-over-year. Q1 ’24 was very much organic in nature.

With nearly 80% of revenue now coming from subscriptions in the just-reported Q1 ‘25 quarter, the company’s growth and financials have become consistent and predictable, resulting in steady gross margins (hovering in the low to mid-80s) and earnings. This transition was significant, and many other software companies in business since the perpetual license days embarked on a similar journey, sacrificing near-term growth for long-term stability.

The Next Phase

Once on subscription licensing, managing customers and negotiating new deals becomes easier for customers financially, as I mentioned earlier. However, these negotiations typically still involve a single product with a fixed number of users or license consumption metrics. This means if a customer wants to add on a different product from the same vendor, the negotiations and sales cycle essentially start from the beginning, creating an environment ripe with friction in the sales process.

But what if a vendor allowed you to use all of their products at any given time for one negotiated subscription cost?

This is the next phase, and it’s only just starting to unfold now at scale.

Financially, this works similarly to a credit line you’d get with a credit card. A company says your credit limit is $5,000, and each of the products costs $150 per seat, device, or the license metric (like a server, processor, database, etc.). Meaning ten users or devices would consume $1,500 of a product, leaving you with $3,500 in credit to spend on other products or additional usage of the same product. In some instances, you can return the usage and switch it for something else, and move the credit around. Some companies utilize a token system where each product’s value is worth a certain number of tokens, and when in use, it pulls those tokens from the pool and uses them. Many times, they can be returned when the usage of that product has stopped for the moment (perhaps after an hour), and the tokens are returned to the pool, ready to be drawn again to any product. This model enables flexibility in launching new apps and utilizing new tools without a sales cycle - a win-win for both the customer and the vendor.

This transition is currently underway at two major cybersecurity vendors: CrowdStrike CRWD 0.00%↑ and, more recently, Zscaler ZS 0.00%↑ .

CrowdStrike has stated it has been a highly successful endeavor, creating a substantial runway for growth with existing customers and a broader landscape for new customers to engage in. They refer to their credit-based/token-based subscription model as Falcon Flex. It has turned out to be a sales machine in and of itself:

Re-Flexes, 39 Flex customers have already deployed their initial contract demand plan and have returned to us for a re-Flex. These customers' initial Flex contracts were 35 months, nearly 3 years on average, and within just 5 months, they came back to CrowdStrike wanting more of the Falcon platform…

— George R. Kurtz, CEO, CrowdStrike’s Q1 ‘26 Earnings Call

This transition, while not as disruptive as moving from perpetual to subscription licensing, is another transition that creates headwinds we can take advantage of when they turn into tailwinds - staying a step ahead of the growth that’ll be seen later. This will occur in approximately the same amount of time as the original sales transition (CrowdStrike is in its second year of this transition), allowing us sufficient time to observe its development.

In the weeks ahead, I will delve into CrowdStrike and Zscaler’s transition to the new sales model and analyze its impacts, as well as the slower growth in the near term.

The bottom line is this new sales model may provide an opportunity to invest if the market sees the sacrifice in the near term and shares pull back. So far, this hasn’t happened, as the charts show sentiment hasn’t yet completed to the upside; however, an opportunity in the future looks to be not too far away.